Exhibition guide

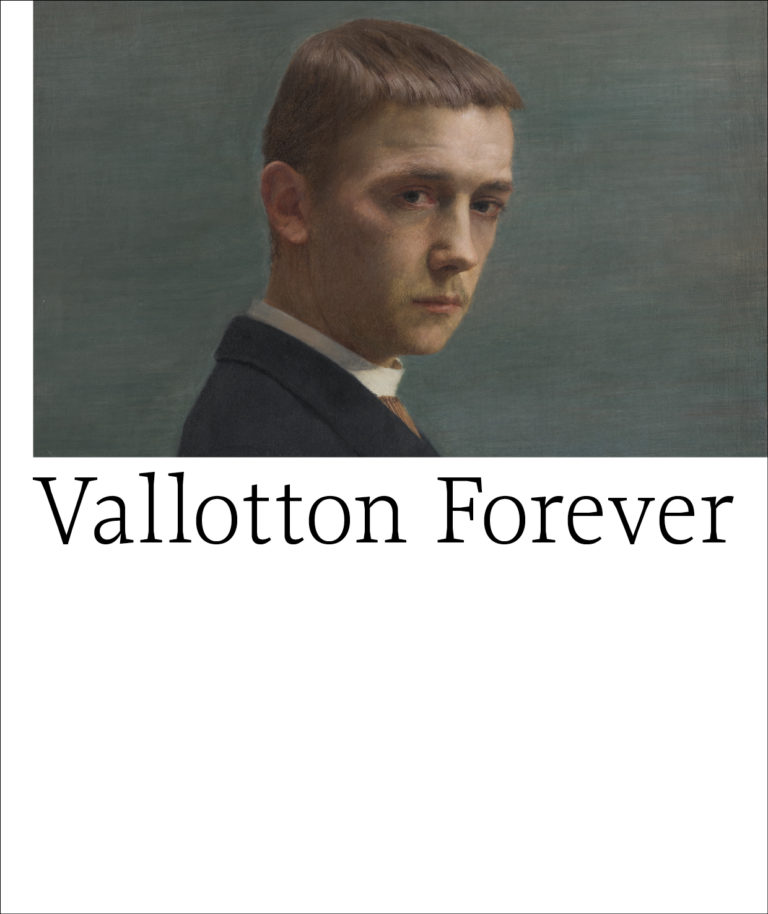

Vallotton Forever. The Retrospective

Lausanne, the artist’s birthplace, is hosting the largest retrospective ever devoted to Félix Vallotton (1865–1925), marking the centenary of his death.

Brought together at the Plateforme 10 arts district, the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, home to the world’s most important collection of his works, and the Fondation Félix Vallotton, a centre for documentation and research, have joined forces to present a fresh approach to this leading figure of modernity, known for his lucid mind, critical spirit and biting humour. For the first time, a chronological and thematic display covers every facet of Vallotton’s creative output, offering a comprehensive view punctuated by masterpieces from Swiss and European collections.

The exhibition first traces Vallotton’s efforts to make a name for himself in Paris, where he arrived at the age of sixteen: his early appearances at the official Salon; his breakthrough as a wood- engraver; his press drawings, which testify to his commitment to social struggles, along with his book illustrations; and finally, his famous interior scenes. In 1893, Vallotton joined the Nabis and fought on the side of the post-Impressionist avant-garde for a symbolist and decorative art.

The second part focuses on the revolution that occurred when Vallotton, much to everyone’s surprise, turned to the realist movements of his time. With his reputation firmly established, he now devoted himself exclusively to painting. His subjects re-examined the traditional genres: nudes, portraits, landscapes, still lifes, and history painting. His dialogue with past painters, his carefully considered compositions, and his vibrant colours envisioned a future for figurative painting at a moment of crisis. From 1905 until his death twenty years later, Vallotton worked apart, completely independent of the modernist movements.

An artist who captivates us and inspires fellow creators, Vallotton is forever.

1st floor

1. Beginnings

Félix Vallotton left his native Lausanne at the age of sixteen to go up to Paris, driven by the dream of becoming a painter. There he began his formal art training at the Académie Julian. In 1885 he started exhibiting his work at the official Salon, where he showed painted portraits in a realist vein like his Autoportait à l’âge de vingt ans.

A turning point came in the 1890s. In 1891 Vallotton contributed to the Salon des indépendants. The following year he took part in the Salon de la Rose-Croix where he exhibited his first wood engravings and it was these that caught the eye of the Nabis (‘prophets’ in Hebrew). In 1893 he joined this group of young artists that included Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis and Édouard Vuillard. Together they championed a symbolist and decorative art.

Vallotton’s style was radically transformed by this. At the 1893 Salon des indépendants, he presented new wood engravings that inspired unanimous enthusiasm whereas two paintings, including Le bain au soir d’été, drew titters from the crowds. With its flat blocks of bright colours and symbolism tinged with irony, this Nabi picture marks his definitive break with the realism of his early work. The same year in Switzerland, the artist exhibited La malade, a work whose subject and style are more in harmony.

2. The crowd

In 1891 Vallotton learned wood engraving under the anti-authoritarian artist Charles Maurin. He developed a forceful style grounded in a fusion of forms and the bold contrast between blocks of black ink and white reserves, i.e., those areas of the paper left untouched by the printmaker. He was soon recognised as the most talented innovator working in this ancient technique.

From 1892 on the crowd proved to be his favourite subject. Vallotton studied masses of people as they appeared in the street, parks, shops, performance halls and venues, and large demonstrations. The series of zincographs called Paris intense features no less than 222 figures, an unheard-of density in print imagery. The artist explored the same themes and used the same print vocabulary in his illustrations for newspapers and books, where his drawings, starting in 1894, were reproduced using photoengraving. His growing reputation meant that popular weeklies with substantial print runs like Le Courrier français and Le Rire now came calling.

In 1896 Octave Uzanne published an exceptional work for book collectors and bibliophiles called Les Rassemblements. He commissioned Vallotton to create 30 drawings of crowds and mobs in the French capital. By taking in the modern city at a distance, as it were, where bodies press together, cross paths, push and shove, the artist is able to offer a view of the crowd that is critical and poetic at the same time.

3. Humour

Vallotton’s humour stands out especially for its irony. Rather than mere caricature, which the artist only rarely employed (his portrait-caricature Pierre Loti or Le véritable jeu des trente-six bêtes), Vallotton had a natural aptitude for allusion. The precision of his line, the economy of the means he deploys and the unexpected framing he liked to devise point up the ambiguity of the images and absurdity of the situations he observed in day-to-day life. He explored a range of registers, from sarcasm to ribaldry, sometimes just to bring a smile to his viewers’ faces.

His work with Jules Renard brought together two men who shared the same sensibility. In both, humour springs less from exaggeration than restraint, less mockery than an amused distance to human fragility and failings.

In 1895 for Nib, the humour supplement of La Revue blanche, Vallotton’s drawings precede and inspire the writer’s commentary, upending the traditional hierarchy of text and image. The two friends’ congenial association carried on until 1902 with Vallotton becoming Renard’s official illustrator, and culminated in the definitive edition of the latter’s short autobiographical novel Poil de Carotte, where his irony is right in tune with the artist’s simple stripped-down style.

4. Spectacle

Like his fellow Nabis Édouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard, and Maurice Denis, Vallotton contributed to the innovative experiments being carried out at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre, hub and holy of holies of the Symbolist movement. Founded in 1893 by the actor Lugné-Poe, L’Œuvre, as it was known, initially promoted Northern European theatre. In 1894 Vallotton designed the programme (done in lithography) of August Strindberg’s Père and the following year the Henrik Ibsen ‘mask’ for an album.

The world of the stage piqued Vallotton’s interest beyond this work with an avant-garde theatre and troupe. He published depictions of actors and actresses in La Revue blanche and Le Cri de Paris (Little Tich, La Belle Otero). Although he does represent shows themselves (Femme acrobate), it is especially the effect they have on the audience that draws his attention. In his poster for the review Ah ! La Pé… La Pé… La Pépinière !!!, or the wood engraving Le couplet patriotique, he focuses on the reactions of viewers, namely the applause, songs, or shouts.

Vallotton also had an eye out for the intrigues taking place away from the footlights. In La loge de théâtre, some sort of drama seems to be playing out between a man and a woman, which is only suggested by the white-gloved hand emerging from the shadows.

5. La Revue blanche

From 1895 to 1902, Vallotton was the official draughtsman-illustrator for La Revue blanche. A hotbed of intellectual excitement, this anarchist-minded periodical, one of the most influential in the late 19th century, defended the artistic avant-garde. In its pages Vallotton published small portraits of literary and artistic figures done in India ink, most often working from a photograph. The approach was a hit. Over three hundred of these ‘masks’ appeared in print in a dozen newspapers and were brought together in two volumes of Remy de Gourmont’s Livre des masques, published 1896 and 1898.

A circle of artists, the Nabis, and a network of writers gravitated around the review. Misia, the wife of the review’s director, Thadée Natanson, was their muse. A wonderful performer, she would play the piano for her friends, whom she often hosted at her flat (La symphonie). In November 1898, La Revue blanche publications brought out Intimités, a series of ten wood engravings capturing scenes in the love lives of various figures playing out in bourgeois flats. These plates are the most accomplished expression of Vallotton’s synthetic style in wood engraving, a medium he was to abandon soon afterwards.

6. Fashion

Between 1893 and 1898, working secretly for La Mode pratique, Vallotton earned a living as a fashion illustrator, a breadand-butter job that was nevertheless to influence his entire output as an artist. The work enabled him to develop a real clothing and accessories vocabulary that would feed into his engravings, illustrations, newspaper drawings, and paintings.

The artist uses fashion as a social repertoire, a handy way to highlight hierarchies, distinctions and tensions between the individual and the collective. Clothes allow him to indicate identity, status, and social category. Parading through his scenes are police and military uniforms, workman’s coveralls, priestly cassocks, coachman frock coats, and the cutaway coats and top hats of bourgeois gentlemen.

At the heart of this flood of humanity, the Parisian woman holds a special place. A strong visual cue in the crowd, her figure is recognizable thanks to her oversized leg-of-mutton sleeves, a very visible sign of female power. The hat completes her elegance, occasionally exaggerating it to the point of grotesquery. The shop, that temple of femininity, is clearly the point where desire, consumption, and the careful staging of appearance take alluring shape; meanwhile, the shop window is the interface between urban space and this closed world where she is the reigning queen.

7. Repression

An anarchist sympathiser, Vallotton found in wood engraving a privileged medium for expressing his leftist liberal convictions whilst contributing through his visual work to the struggle against social inequalities. Plates like La charge, L’anarchiste, and La manifestation decry the brutality of the police.

In 1894 Vallotton’s political activism began to shift to the drawings he was doing for newspapers, and from then on he would limit the expression of his commitment to equitable justice based on equal rights. From its founding in 1897, he contributed to the Cri de Paris, one of the rare periodicals to call for a review of Captain Dreyfus’s trial. Unjustly convicted, Dreyfus had been sentenced to be deported to a penal colony for life. Vallotton had several drawings published on the newspaper’s front page denouncing, like Emile Zola’s J’accuse…!, the antisemitic conspiracy (L’Âge du papier).

In 1902 Vallotton produced 23 lithographs under the overall title Crimes et châtiments for a special issue of the review L’Assiette au beurre. Through these images and their captions, the artist violently denounces abuses of power and the disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted. Bosses, property owners, landlords, husbands, parish priests, and officers of the law are lambasted with relentless severity.

8. Interiors

In 1896 Vallotton began to focus on interior scenes in his wood engravings (Le bain, La paresse). Soon after, however, he decided to devote himself completely to painting, his first calling. At an 1899 Nabis exhibition at Durand-Ruel’s gallery, he showed six Intérieurs avec figures, masterpieces of his Nabi period (including La chambre rouge, La visite, Cinq heures, and L’attente). Each of these paintings features a man and a woman surprised in unclear situations that encourage us to imagine what lies outside the framed view. The setting and accessories are also players in the drama whilst the power of the colours contributes to the intensity of the emotion.

During these same years Vallotton more and more turned to depicting women undressed. He shows them in their bedrooms, in brothels, and at their toilet.

Following his marriage to Gabrielle Rodrigues-Henriques in 1899, the artist also began focusing on daily life. His wife is featured in the intimate setting of the home (Intérieur avec femme en rouge de dos, Femme fouillant dans un placard). His stepchildren appear in works that suggest the tensions inherent in the life of a blended family (Le dîner, effet de lampe).

2nd floor

9. The nudes

Vallotton painted his first nudes during his art studies but it was not until the Nabi years that he would return to the female nude, presented without any modelling of light and shade and therefore without volume. A transition began to take shape in 1902 that became more pronounced in 1904 when the artist would produce several bronze statuettes. It was this experience that reawakened his interest in volume.

At the 1905 Salon d’automne, the artist showed Le repos des modèles, a manifesto of his return to realism. The nude now becomes his main area of experimentation. He followed this with Trois femmes et une petite fille jouant dans l’eau and Le bain turc, ambitious large-format canvases as well that were first exhibited at the Salon des indépendants of 1907 and 1908.

Over the years Vallotton would depict numerous nude female figures alone or in groups indoors or out, with or without accessories. Some were done directly from models, the artist looking to respect the truth (Torse de femme assise drapée de satin jaune); others were proceeded by preparatory drawings and focused on formal questions (Baigneuse de face, fond gris). Occasionally humour and bawdiness add a touch of spice to these pictures (Femme nue lutinant un Silène).

10. The landscapes

After a break of several years during which he focused on the nude, Vallotton returned to the landscape in 1909. His long stays in Honfleur in Normandy, where he now regularly spent his summers in a rented cottage, played a decisive role in developing his new sensitivity to the mysteries of nature (Le rayon, La mare).

Whereas he had painted his landscapes outdoors until 1900, he now would recreate them from memory in the studio, after the small sketches he dashed off on the spot in notebooks.

Dreaming of ‘a painting freed from all literal respect for nature’, that is, a return to the idealised landscape of classicism, Vallotton was to develop a method based on distancing himself from the subject. This gave rise to what he called the ‘composed landscape’.

The synthesis was to become more pronounced over the years. Forms were refined, the contrast between shadow and light became more intense, and his bright colours moved further away from those seen in reality. A series of sunsets, begun in 1910 and continued until 1918, culminated in radical compositions that were reduced at times to broad parallel bands of colour whose chromatic intensity yielded effects of great expressive force.

11. The war

Vallotton was a renowned artist when the First World War broke out. On 2 August 1914 the order given for general mobilisation was a devastating blow to him. Vallotton, who had been naturalised in 1900, wanted to go to war as well but he was entering his fiftieth year and his voluntary enlistment was refused due to his age. This forced exclusion affected him to the point of his becoming depressed.

During the conflict’s first two years the artist wondered whether painting could portray modern warfare. He opted for an allegorical vocabulary in paintings like Le crime châtié and L’homme poignardé that powerfully condemn the horrors of massacres or give voice to the hope for victory. He also experimented with ‘form studies’ on the fragmentation of bodies (Quatre torses).

In 1917 Vallotton requested an artistic mission from the army and travelled to the Champagne and Argonne fronts. This brief tour filled him with new creative energy. Verdun, a large-format painting completed in December 1917, was his ‘interpreted war picture’. In it Vallotton achieved a pictorial synthesis that is freed from any literal reference to reality. The piece contrasts sharply with contemporary depictions of the hell experienced by the soldiers in the trenches.

12. Final years

Vallotton worked tirelessly right up to the end of his life. Landscape, the vital core of his practice since 1909, remained his favourite subject. He deepened its synthetic scope by playing with the monumentality of the forms, the richness of the colours, and the simplification of the lines. On the banks of the Seine and the Loire, he rendered his impressions of nature in simple motifs steeped in calm and silence, where a feeling of serenity dominates.

At the same time, he regularly produced still lifes, the genre becoming increasingly important within his output. Vallotton zeroed in on the density of objects, their weight, volume, and texture, to reveal their material presence with a new intensity. Fruit, vegetables, eggs, and flowers became independent subjects the artist imbued with quiet power.

From 1920 on the artist would winter in Southern France. The warm light and mild climate proved stimulating to him and illuminated his pictorial output. He stayed for several months each year in Cagnessur-Mer with his wife, Gabrielle. In 1921 he noted in his diary, ‘Back from Cagnes after a four-month stay that was a dream come true. There I rediscovered the possibility of being happy.’