Exhibition Leaflet

Vallotton. The Ingenious Laboratory

Vallotton’s oeuvre is vast, comprising over 1700 paintings, hundreds of drawings and around 1200 book illustrations and press draw-ings, some 200 prints, and numerous texts. This impressive output is the result of the artist ceaselessly working day after day over some four decades, starting with his arrival in Paris in 1882 and only ending with his death in 1925.

Throughout his career and across multiple mediums, Vallotton worked steadily in reaction to different imperatives. First and fore-most was the vital need, never satisfied, to create and to progress in his craft. It was also for him a matter of fulfilling commissions and meeting the expectations of his dealers, showing up at exhibitions, and, more prosaically, providing for himself and his family.

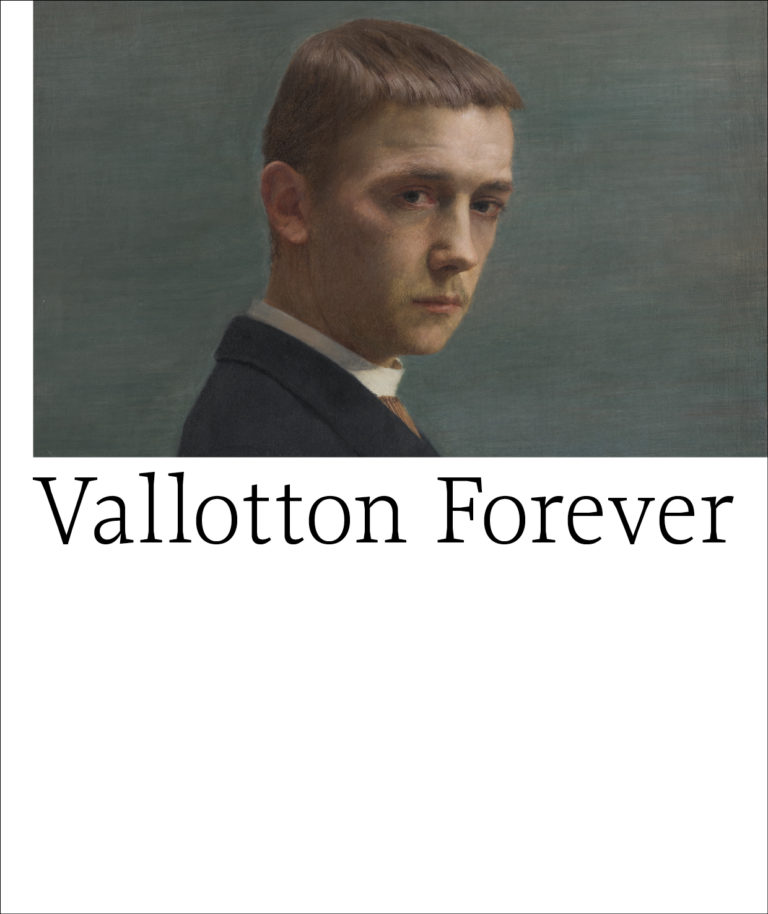

The retrospective Vallotton Forever is currently showing in MCBA’s large exhibition platforms a broad selection of the artist’s most ac-complished works. The associated exhibition Vallotton. L’ingénieux laboratoire [The Ingenious Laboratory] has taken a different tack, proposing to explore the genesis of his creative output, that is, his models, processes, and techniques. The exhibition draws on the extensive collections of MCBA and the Fondation Félix Vallotton to retrace the stages that led from the conception to the making of a work of art.

The layout of the exhibition takes visitors through seven themes in turn that highlight a range of the artist’s skills and imagination, hand and head, including interpretation of the old masters, engrav-ing, landscapes, portraiture from photography, illustration, the nude, and working in large formats.

1. After the old masters

Vallotton left Lausanne for Paris in 1882. To fulfil his dream of becoming a painter, he studied at the Académie Julian. At the Louvre, where his name can be found in the copyists registry, he painted copies of works by Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, and Antonello da Messina. These old masters were to exercise a lasting influence on his own painting, particularly in the art of portraiture.

Copying works hanging in the museum was part and parcel of learning the craft, but it was also for Vallotton a way to earn a living. At a time when reproducing artworks wasn’t yet the sole preserve of photography, he turned out copies for sale to either private clients or the art reviews. Vallotton also did an etching of a portrait and a self-portrait of Rembrandt that are not conserved in Paris and therefore must have occasionally worked after engraved copies done by others.

2. Engraving

In the late 1880s, Vallotton took up engraving on metal. He cut these plates (called ‘matrices’, the plural of ‘matrix’) using dry point and etching. His subjects were intimate and personal, such as his mother, his partner Hélène Chatenay, and views of Lausanne and Paris.

In 1891 the artist began working in wood engraving. After making a preparatory drawing, he would carve a block of wood with a penknife, hollowing out (removing) the areas that were not meant to hold the ink. The constraints of this technique fostered the development of a stripped-down refined style based on simplifying forms and creating seamless contrasts between areas of black and white. These engravings made him famous and established his reputation.

Vallotton only rarely worked in lithography, a technique in which the artist draws his or her subject directly on a limestone matrix. Such was the case in 1902 for a special issue of the review L’Assiette au beurre.

3. Landscapes

After 1900 Vallotton no longer painted landscapes outdoors. With rare excep-tions (Sous-bois à Varengeville [Under-brush in Varengeville]), he did them rather in the studio, working from his annotated sketches or very simple drawings.

By the sea or on his walks in the country, the artist filled his notebooks with small pencil drawings, quickly taking down the essential lines. He would note the reference of the colours in front of him thanks to a numerical system. Back in the studio, he then transferred these indications to the canvas, reconstructing the landscape but from a distance. In what he called the ‘composite landscape’, nature is reinterpreted and ordered according to his personal vision. This two-step process afforded him great freedom in synthesising forms and interpreting colours, lending his paintings the decorative artificiality that is their hallmark.

4. Based on photography

The advent of photography was one of the most significant events of the second half of the 19th century. Vallotton took an interest in the new medium. At first he worked from photos shot by others to create his portraits, whether they were drawn, painted, or engraved (Portrait du graveur Félix Vallotton par lui-même [Portrait of the Engraver Félix Vallotton by his own hand], À Edgar Poe [To Edgar Poe]). The art critic Julius Meier-Graefe saw in the artist’s turn to photography the explanation of his ability to recall the most characteristic features of a face.

In 1899 Vallotton acquired a Kodak Bulls-Eye camera. From this point on, he would shoot his own photos when preparing some of his pictorial compositions. More than mere documents, these images made it easier to transfer volume to a flat surface. This was a principle lying at the heart of his aesthetic since his Nabi period.

5. Illustration

In the late 1890s Vallotton regularly took ornamental work, especially for a number of German publishers. The plant and animal worlds inspired his decorative vocabulary. For the 1897 edition of Der Bunte Vogel, an almanac whose cover that year was designed by Vallotton, the artist dreamed up a whole repertoire of vignettes teeming with stylised birds.

This taste for ornamental motifs can also be seen in his advertising projects, where his talent as an illustrator as well as a graphic designer is amply on display. For Chocolat Kohler, a company in Lausanne where his brother, Paul, worked, Vallotton came up with an advertisement that was published in the weekly Le Cri de Paris; image and lettering complement each other, forming a decorative whole. The artist also designed a number of packaging projects for Chocolat Vallotton, his father’s chocolate factory, which was also located in Lausanne under the present-day Chauderon Bridge.

6. The nude

The very high number of drawings of female nudes that figure in Vallotton’s output attests to the essential place the subject enjoyed in his art. These works were drawn from models on loose sheets of paper and most often in grey pencil. There is great variety in the poses with the nude subject reclining, seated, seen from the rear, leaning, or on a stool.

For his ambitious paintings which sometimes included several figures, Vallotton, before beginning to paint in oil, would do very elaborate and detailed drawings (Étude pour Le bain turc [Study for The Turkish Bath]). As in his landscapes, he would transfer them to the canvas in a second phase, one that he clearly differentiated from the initial act of observation. Vallotton also occasionally painted the nude directly on the canvas whilst facing the model and against the backdrop of the studio (Torse nu brun [Brown Nude Torso], Torse au châle rouge [Torso with Red Shawl]). He would do the painting without any preparatory drawings.

7. Large formats

During his Nabi period, Vallotton did small-format paintings, often on cardboard and working in tempera. In 1900 he came back to oil on canvas and standard formats. Monumental works were rare, limited to mythological subjects and allegories.

In 1915 the artist painted a triptych inspired by the First World War and the tragic events of those times. The three pictures are Le deuil [Mourning], Le crime châtié [Crime Punished], and L’espérance [Hope]. The triptych measures 2.5 m high and 6 m wide. To carry out this ambitious project, Vallotton did three preparatory drawings and employed the traditional technique of ‘squar-ing’, which involves making a similarly proportioned pencil grid on both the draw-ing and the much larger canvas where the composition is transferred square by square. The method allowed him to adjust each detail and transpose his sketch whilst expanding it to a monumental scale.