Bibliography

Iwona Blazwick and Sabine Breitwieser (eds.), William Kentridge: Thick Time, exh. cat. London, Whitechapel Gallery, Salzburg, Museum der Moderne, Humlebaek, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Manchester, Whitworth Art Gallery, London, Whitechapel Gallery, 2016.

William Kentridge and Rosalind C. Morris, That Which Is Not Drawn. Conversations, Calcutta, Seagull Books, 2014.

Peter L. Galison and William Kentridge, ‘The Refusal of Time,’ in Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev (ed.), Documenta (13): The Book of Books, Ostfildern, Hatje Cantz, 2012: 104-113.

Born in Johannesburg, South Africa, William Kentridge was deeply marked by the country’s political and social context. He studied political science and theatre before turning to drawing in the mid-1970s, eventually developing a body of work in charcoal that led to his first animated shorts. The drawings for his animations are always produced successively on the same sheet of paper, with the traces of previous erasures and alterations visible alongside the new drawings, reflecting Kentridge’s stance on time and history as non-linear processes.

Anti-Mercator is one of the works Kentridge created in preparation for the installation The Refusal of Time at dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel in 2012. It feeds into his research on the understanding of time and the measuring of space as tools of modernity and instruments of control and power. The title references Gerardus Mercator (1512-1594), inventor of the map projection named after him and author of a chart that proved vital to navigators at a time when Europe was extending its territorial reach. The projection is still used to this day, though it distorts the size of various countries, particularly in Africa.

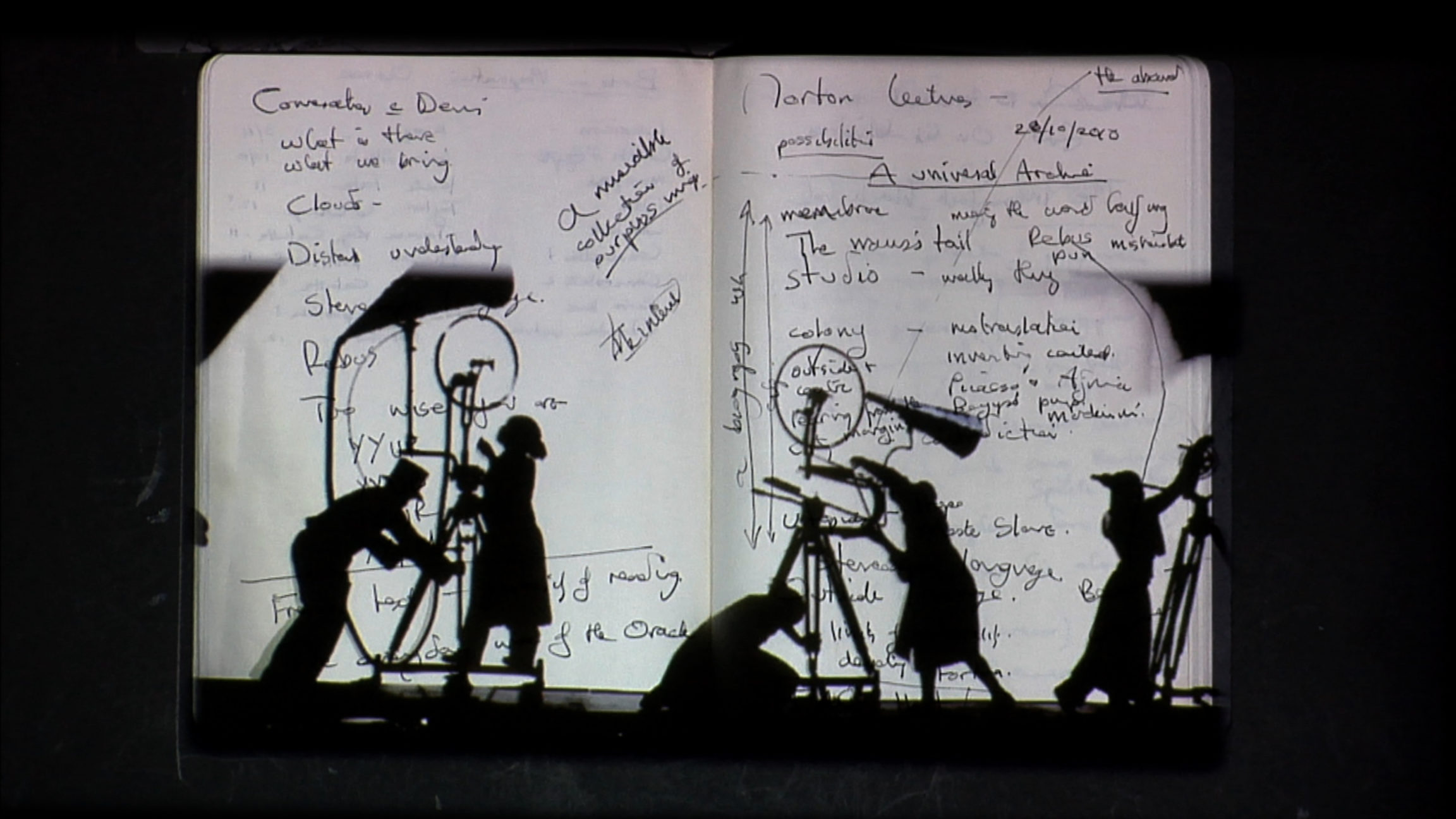

Kentridge’s notebook fills the screen. The artist alternately leafs though it, draws in it, and writes sentences that refer to various conceptions of time and space, from Isaac Newton’s linear time to Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity. A metronome keeps time, voices are heard, music lends the pictures rhythm, and Kentridge himself appears on the screen, walking at the front of his outsized notebook and then running as hard as he can across the pages as they are leafed backward. The film closes with a silhouetted marching band parading across the pages and a couple dancing as if to defy gravity and breathe fresh life into the present moment.