Bibliography

Hans-Peter Wipplinger (ed.), Ferdinand Hodler. Wahlverwandtschaften vom Klimt bis Schiele, exh. cat. Vienna, Leopold Museum, Cologne, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2017.

Oskar Bätschmann and Paul Müller (eds.), Ferdinand Hodler. Catalogue raisonné der Gemälde. Band 3: Die Figurenbilder, Zürich, Institut suisse pour l’étude de l’art, Zürich, Oehy, Scheidegger & Spiess, 2017: n. 1354.

Jura Brüschweiler, ‘Mysticisme et rôle du double dans le “Regard dans l’infini” de Ferdinand Hodler,’ in De Vallotton à Dubuffet: une collection en mouvement, acquisitions, dons, prêts, Les Cahiers du Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne 5, 1996: 12-20.

Ferdinand Hodler met Gustav Klimt and many other artists of the Viennese avant-garde, as well as their collectors, when visiting the Austro-Hungarian capital in early 1903. Aged fifty, the Swiss painter was now internationally known and he was invited back the following year as guest of honour at the Viennese Secession’s nineteenth exhibition. He sent thirty-one works to this exhibition, which marked a turning point in his career. Blick ins Unendliche, numbered twenty-eight in the catalogue, was conceived within this stimulating context.

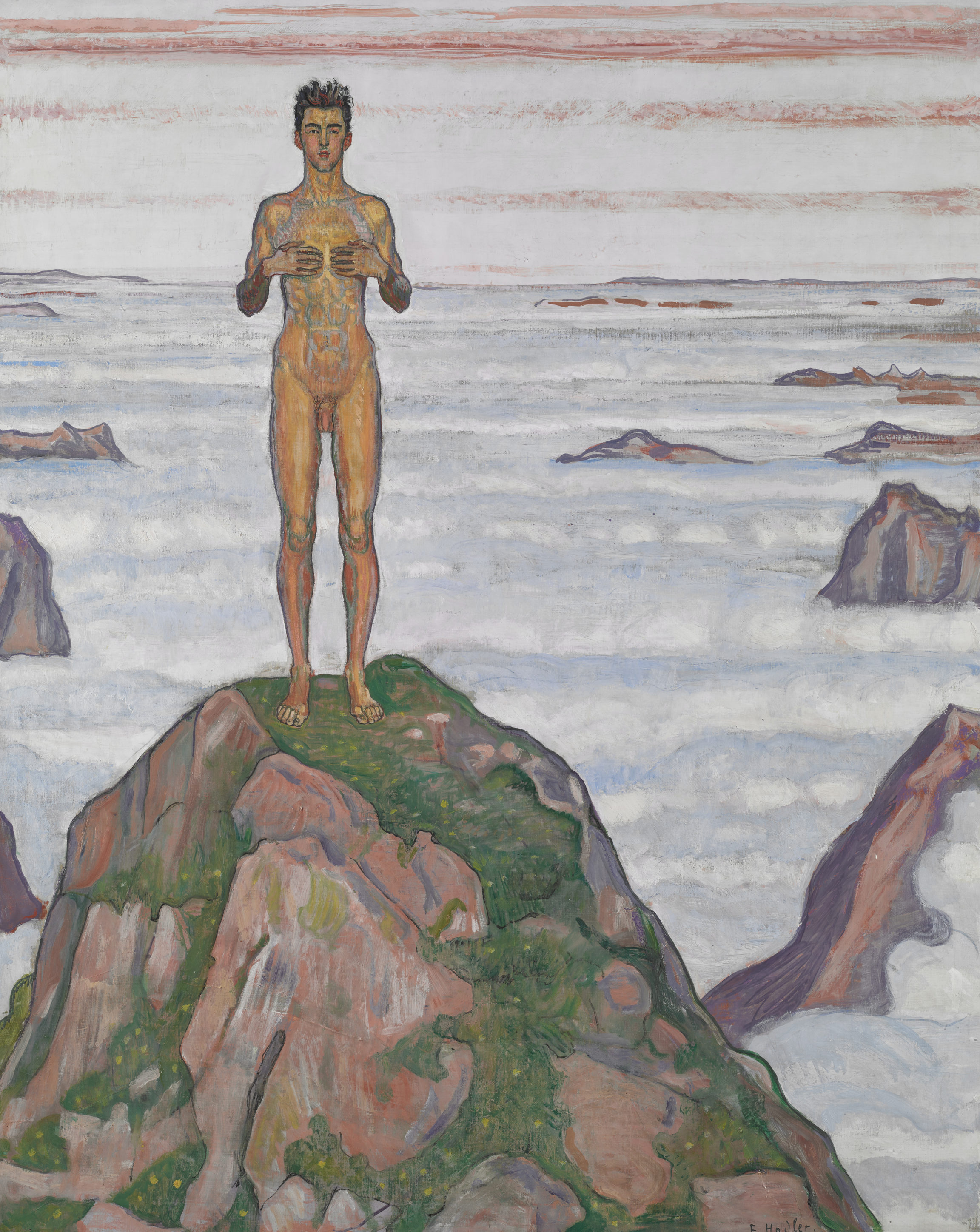

In the foreground of this painting we see a naked young man standing on the top of a rocky promontory. This vertical figure, derived from the traditional representation of stylites (hermits who lived at the top of columns), breaks up the parallel pattern formed by the stylised sea of clouds and sky. The colours are harmonised: cold blue for the air higher up and a warm pink for the rising sun tingeing the scene. The figure, whose model was the artist’s fifteen-year-old son Hector, symbolises the artist’s lofty, far-reaching vision. The hands resting on his chest express the strength and interiority of a physical and mystical communion with cosmic forces. Here, Hodler imagines a veritable hymn to the beauty of youth, itself as eternal, pure and unspoilt as Alpine nature.

This painting was immediately acquired by the Austrian industrialist and art collector Carl Reininghaus after the exhibition in Vienna in 1904, but Hodler insisted that he must first be allowed to put ‘a few finishing touches’ to the work in his studio in Geneva. That was where it was given the form it has today. This picture marks an important stage in representations of the idea of paradise. The Garden of Eden theme was indeed much reformulated in the early twentieth century, as here, where it becomes a place in the upper mountains, out of the reach of modern civilisation.