Bibliography

Julie Borgeaud (ed.), Louis Soutter. Le tremblement de la modernité, exh. cat. Paris, La Maison Rouge, Fondation Antoine de Galbert, Lyon, Fage, 2012: 89.

Hartwig Fischer (ed.), Louis Soutter (1871-1942), exh. cat. Basel, Kunstmuseum, Lausanne, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne, Collection de l’art brut, Ostfildern-Ruit, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2002: n. 116.

Michel Thévoz, Louis Soutter. Catalogue de l’œuvre, Lausanne, L’Âge d’Homme, Zurich, Institut suisse pour l’étude de l’art, 1976: n. 2392.

![Inconnu [Suisse occidentale], Sainte Anne enseignant la Vierge (Saint Anne Teaching the Virgin to Read), c. 1550-1580](https://www.mcba.ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/215_INCONNU_num4000_nr-768x1024.jpg)

Soutter was interned in Ballaigues, where he suffered cruelly from the narrow confines of his existence. He adopted an ascetic way of living, forcing himself to fast and go on long walks. He escaped into his imagination, elaborating countless plans to regain his autonomy: ‘I want to enter into the life of all beings … and earn an honest living with my music and my drawings’, he wrote to his brother around 1924. In about 1927 he met his cousin Le Corbusier. The encounter would prove decisive: saying he was dazzled by Soutter’s drawings, the architect published an article about him in the avant-garde journal Minotaure in 1936 and organised an exhibition of his works in the United States. With the attention of a small circle comprising his friend Yvonne Walter-du Martheray, the painters René Auberjonois and Marcel Poncet, the writers Jean Giono and Charles Ferdinand Ramuz, the publisher Henry-Louis Mermod, and two gallerists in Lausanne, Claude and Maxime Vallotton, Soutter recovered his confidence. This was reflected in a significant change in his art.

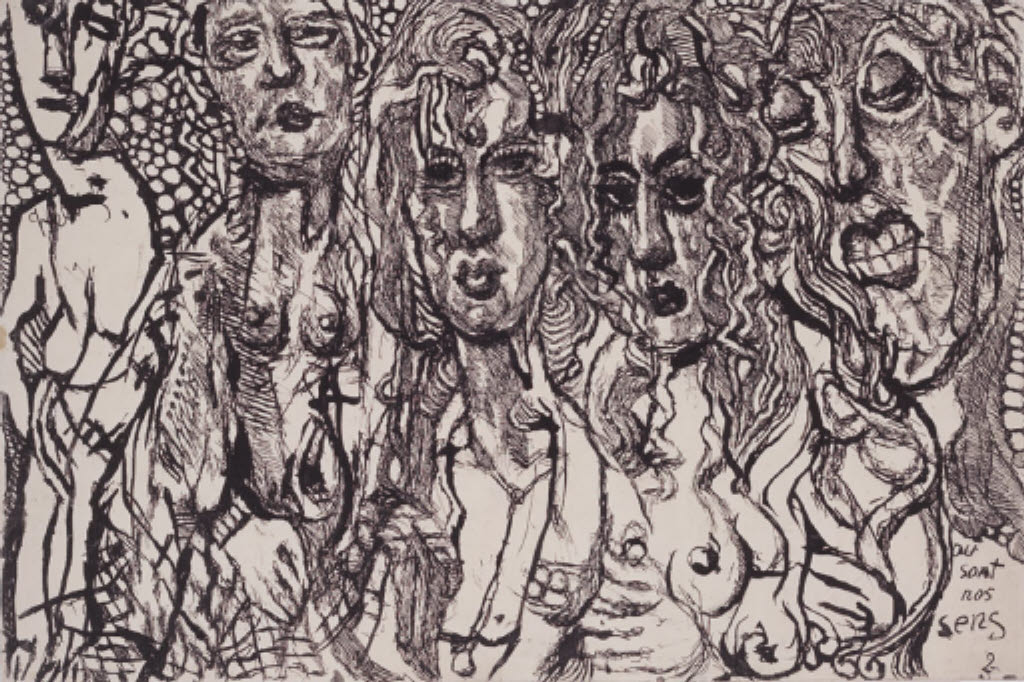

The works produced by Soutter in this period are called ‘mannerist’ because of their new expressiveness and formal distortions. The artist drew in Indian ink, increasing the size of his sheets. Où sont nos sens? belongs to a series that is peopled with alluring and suffering creatures inspired by the residents Soutter had observed in the asylum. He called them the ‘Without God’: ‘… creatures in pain, a pure caste, raised up by the torturing sickness of isolation.’ The women are naked, their only ornament a necklace and a huge head of hair; they display their teeth and made-up lips, their hands alternately hiding and caressing their sex. They strike lascivious poses, teasing the men who vie for their attention. In Ballaigues, these drawings, which speak of the artist’s emotional solitude and sexual distress, earned Soutter the nickname of ‘the mad pornographer’.