Bibliography

Sebastian Baden and Luise Leyer (eds.), Martha Rosler. In One Way or Another, exh. cat. Frankfurt, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Berlin, DCV Verlag, 2023.

Darsie Alexander (ed.), Martha Rosler. Irrespective, exh. cat. New York, Jewish Museum, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 2018.

Elvan Zabunyan, Valérie Mavrikorakis and David Perreau (eds.), Martha Rosler. Sur / sous le pavé, exh. cat. Rennes, Galerie art et essai, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2006.

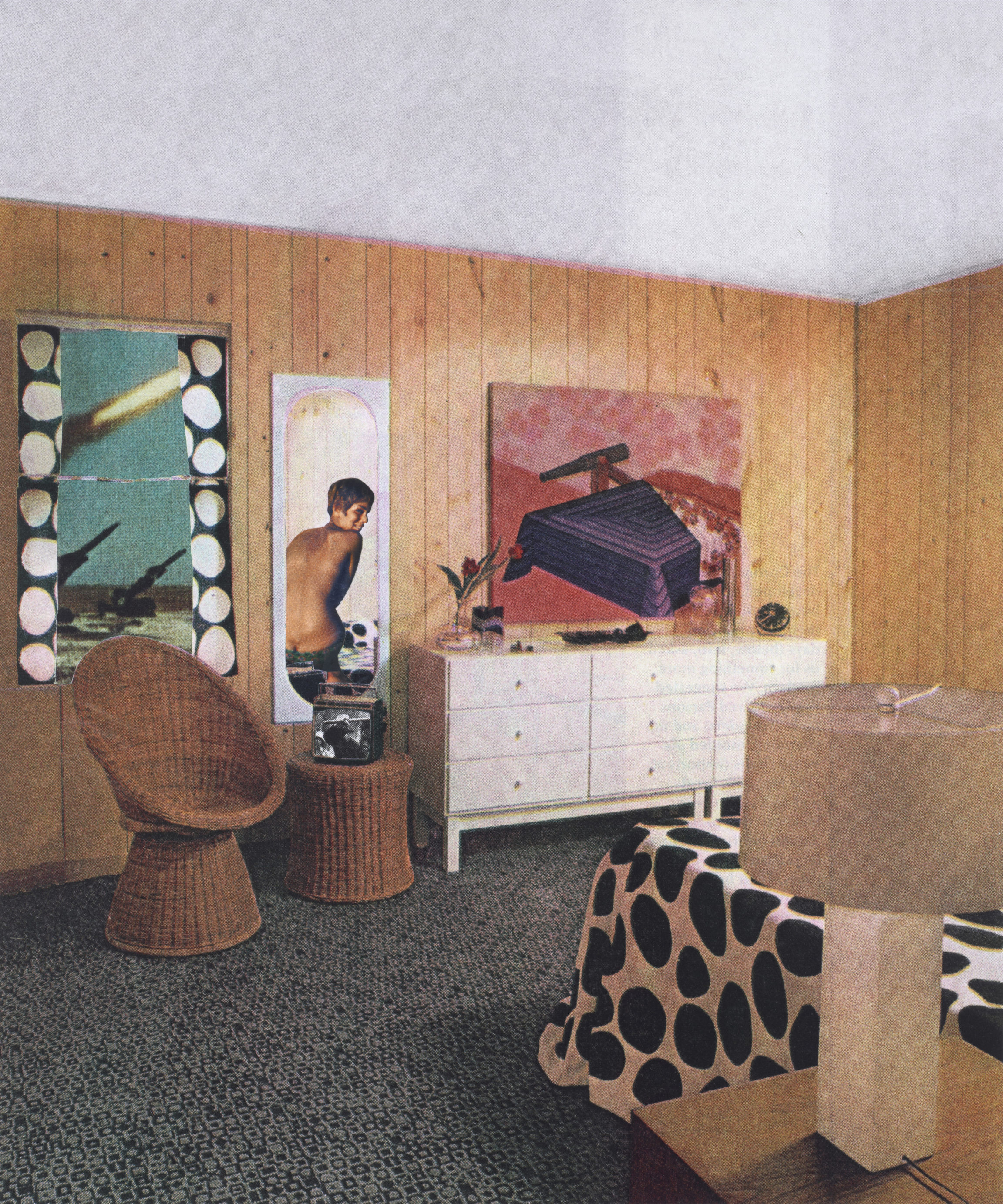

Martha Rosler initially trained in painting before turning to photography as a student at the University of California San Diego. The years from 1967 to 1972 saw her working on a series of photomontages she titled Bringing the War Home, including this work, Woman with Cannon (Dots). For the series, she juxtaposed and re-photographed news images clipped from Life and interiors from House Beautiful, circulating the photomontages outside the traditional art circuit in underground zines and feminist publications. The series was part of a broader art movement reacting to the war in Vietnam, the first to enter homes via television screens. Rosler here joins a long tradition of politically motivated photomontages dating back to the 1920s and 1930s in the work of artists like Hannah Höch and John Heartfield.

Woman with Cannon (Dots) features a white woman clipped from an advertisement or men’s magazine reflected in a bedroom mirror, between rocket fire and a telescope trained on her. The work generates a clash between two spheres of human existence – the Vietnam war and American homes – that the media obstinately sought to keep apart. The female body is framed not only by military apparatus, but also by a specific artistic aesthetic, as the polka-dot fabric of the bedcover and curtains gestures to Pop Art. As Rosler said in 1983, “In Pop, the female appears as a sign […] assimilated both to the desire attached to the publicized commodity form and to the figure of home”. Here, she underscores how, time and time again, art and advertising produce an image of womanhood shaped by gender expectations, which she calls into question to highlight the political dimension of domination in all aspects of life in society, both public and private.