Exhibition Leaflet Mirage

The BCV Art Collection invites Natacha Donzé Gina Proenza Jean-Luc Manz Denis Savary

29.9.2023 – 7.1.2024 Espace Projet

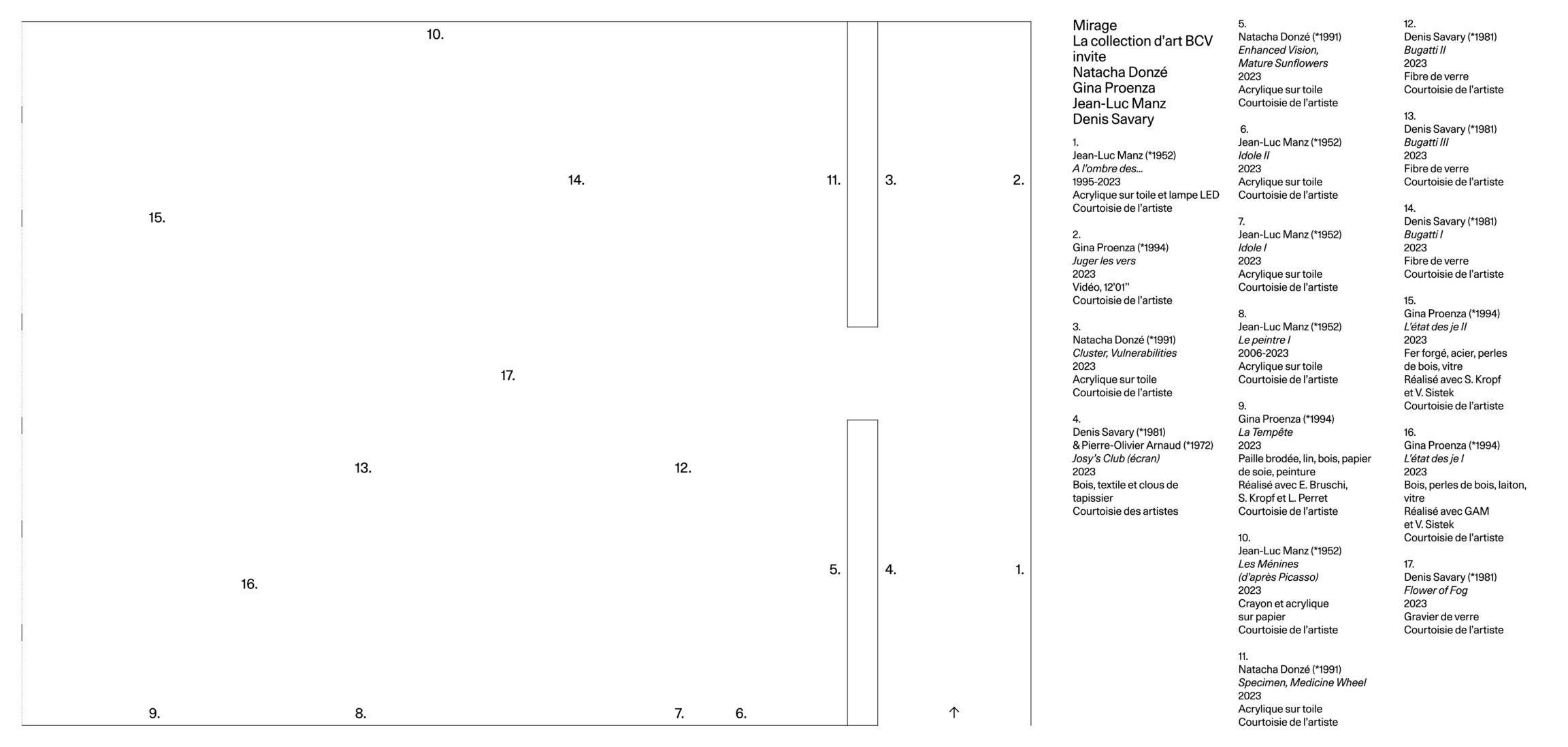

Mirage invites us on a journey, one that goes from shadow to light through new and emblematic works by four invited artists. They have been brought together by the BCV Art Collection for its second show in the MCBA’s Espace Projet gallery. For Mirage, the BCV Art Collection commissioned works from Natacha Donzé, Gina Proenza, Jean-Luc Manz, and Denis Savary. This is a first for the bank’s collection after over fifty years of existence. BCV is betting on a multifaceted exhibition as a work in progress. The aim is to break free of the usual practice of displaying what has been acquired to more fully embrace what is being created now and support the contemporary art scene.

Over the course of group work sessions – which were both demanding and exhilarating – one idea came to the fore with absolute clarity, that of locating the future artworks in an invented landscape; today that notion serves as the narrative through line for the show. Conceptually, this means bouncing around the apparently simple idea of bringing together in one venue several practices while avoiding an overarching theme that is mere pretext – in order to suggest, and be open to, a pertinent experiment and experience in both visual and formal terms. Hence our decision to modify the size of the gallery, dividing it into two distinct spaces. There is a corridor designed to serve as a gap and existing as a prelude, an introduction to the program of the exhibition, which plays out in the main gallery. There the floor is covered with a transparent glass gravel that concentrates the show’s themes and, doing so, better conveys them, like a blank canvas stretched over a frame. Flashes of light from the translucent material, as much as the subtlety of the correspondences among the works hanging on the walls and displayed on the floor, reveal through their intensity an infinite number of perceptions that are similar to a mirage. Visitors’ walking around the show, like the sound of their steps in this fictional territory, renews the uncanny effect, inviting viewers to take a closer look and wander through the space once more.

From exhibition design to displaying artists and their works

By Catherine Othenin-Girard

DENIS SAVARY (*1981) uses a fairly broad range of mediums that runs from drawing and sculpture to installation and video art. In one register that is all quotation and allusion, Savary references both art history (most often Surrealism) and the field of literature, playfully grounding his work in a hybrid- isation of sources as well as genres and techniques. Shunning all hierarchies, the artist relies on craftsmen and technicians to produce his pieces, thus valorising a manufactured output in favour of the show as a work of art in and of itself. For this museum project, the series of anteaters called Bugatti, I, II, III takes up a recurring subject in the artist’s practice, i.e., animal sculp- ture. Here Savary is referring to the Bugatti dynasty: Carlo, the father who designed and produced animal-like Art Nouveau furniture, and his two sons, Rembrandt, an animal sculptor, and Ettore, the creator of the famous make of automobiles that bears the family name1. Savary sees in these three figures “something like a portrait and mirror of his practice”. And indeed, all of them are drawn to the fantasy genre and are interested in an industrial look in their respective outputs. The blue Savary has chosen is a nod to the emblematic models of the brand and making the pieces out of fibreglass allows him to turn out numerous variants while suggesting the strange animal’s movements. Among the many iconographic sources the artist considered for this series, one could mention a famous 1969 photograph of Salvador Dalí coming out of the Gaîté Station of the Paris metro with an anteater on a leash. Savary’s arrangement here recalls the ties of friendship that bound Dalí to André Breton in the 1930s, whom he called the “Great Anteater”, because of the phobia they both felt for ants. And, as in Savary’s practice as a sculptor, the importance of animals as objets trouvés in the Surrealist movement cannot be denied. In a similar register, Savary created the glass gravel surface which recalls the materialisation of the effects of weather in earlier shows. Flower of Fog, for example, was something between snow and fog. Borrowing its title from a drawing by Meret Oppenheim, who was also affiliated with the Surrealist movement, it conjured up our connection to the landscape, which is both physical and mental. This particular art material demystifies in a way the museum space in favour of a future territory. Moreover, Savary’s interest in vernacular objects from the domestic sphere, like the fireplace cover he once exhibited (Josy’s Club, 2023) springs from the same rejection of current aesthetic categories and the same desire to identify art with life. In this, he is approaching the neo-Dadaist spirit of Fluxus, an inescapable movement on the Swiss-French art scene since the 1970s, notably around the singular figure of John M Armleder.

For the Mirage show, JEAN-LUC MANZ (*1952) harks back to Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656), which is considered an absolute masterpiece of Western art history. Why then does Manz take such an interest in a work that apparently is so removed from his practice as a painter of geometric abstraction? The explanation surely lies in the historiographic context in which this picture was executed. When Velázquez, then the most important court painter in Spain, was carrying out this commission from the monarch, Philip IV (1621-1665), he was at the high point of his career. In this large-scale work, we see the artist painting a group portrait of the royal couple – the reflection of the monarch and his queen is subtly included thanks to a mirror in the background of the composition – as well as the infanta Margarita Teresa, surrounded by her retinue and other dignitaries. Endlessly analysed and commented on by the greatest art historians since its completion, this picture is in a category all its own thanks to its magisterial craftsmanship seen in the Spanish painter’s mastery of perspective and brushwork. But in addition to these indisputable technical criteria, it is the variety of the vision offered up by Velázquez that has intrigued viewers ever since. Indeed, the play between the “front” and “back” of the painting confounds interpretation. Of course we see a genre scene before us but we also see a painter honouring his commission, while depicting himself in the process of painting. Recent research using X-ray imaging reveals, moreover, that the depicted Velázquez was in fact absent from the first version of the composition, and that this modification proved very bold for the time. These latest efforts to delve beneath the surface allow us to comprehend this monumental creation not only as a scene of major cultural and political importance, but also, as Daniel Arasse suggests, as a narrative fiction that was extremely novel in its day and age. We could liken it, relatively speaking, to a history of painting at a given period. And it is exactly that assertion that interests Manz. We might also point out that other artists, and not minor ones, have been inspired by Velázquez’s picture. Pablo Picasso produced 44 versions of Las Meninas between August and December 1957, essentially focusing on the figure of the infanta, whom he refashioned into the main character, while breaking down and recomposing the subject in his own way. Manz has seen this series in Barcelona’s Picasso Museum so it is part of his iconographic references. But how then did he approach and interpret these two “monuments” for the Mirage invitation? Initially, he did different sketches in his notebooks, centring his breaking down of the picture on both the geometrical structuring of Velázquez’s vast composition and, like Picasso, the visual importance of the back of the canvas being painted in the work. The concept of the “painting within the painting” then became the element around which he worked out his own iterations. First, in 44 paintings on paper in reference to Picasso’s Las Meninas that take shape from a rigorous grid pattern of light lines, a chromatic selection of bright hues, and a series of associations combining squares, triangles, and other generic geometric motifs. This series amounts to a commentary, as if the artist were studying each of Picasso’s 44 versions in order to bring out the elective element in each which he then paints on a canvas. Next, he tackles the subject through two simultaneously distinct yet complementary works. For Peintre I, he dares to take on the monumental format of the original painting (318 × 276 cm), depicting to scale the back alone of the blank canvas, left white against the monochrome black background. For Peintre II, he does four 1:10-scale paintings, returning to the same motif, but this time he selects coloured backgrounds in keeping with his chromatic range. And, in Arasse’s words, as “time does not exhaust Las Meninas, it enriches it”, this serial interpretation underlines the visual research Manz has carried out over decades, consisting of activating doing to foster being, daring more in order to continue to produce. And we can bet that he holds to that position right up to choosing a title that is nothing less than the portrait, even the self-portrait of the painter in the generic sense of the term. Finally, the pieces called Idole I, II and À l’ombre des… complete the quotational side of these works while pointing up the influence of both ancient art and the art that is the monochrome adventure running through his work. Not to mention the visual identity of the French daily Libération, which has become an inescapable and essential graphic mould for Manz’s output.

The experimentation being done by NATACHA DONZÉ (*1990) is above all the work of a painter who both interrogates and raises again and again the fundamental question of the flatness of the painted surface. Each project is structured in such a way as to define precisely the allotted pictorial space and thus enable the work to question the place where it is being shown. In the case of Mirage, she has selected two walls on the southside of the gallery and has divided up her contribution to the show into a series of pictures in a range of formats. Like a puzzle, these paintings can be brought together and can potentially occupy all of the wall space normally allotted to paintings, or be spread out to play with spacing and gaps, like a changing architectural composition. This combinatory complexity works like a strong light that reveals the practice of an artist who excels in rendering illusionistic arrangements and even trompe-l’oeil effects. This multifocal aspect of her art shakes up the levels of reading and interpreting the work, and generates a visual sensation that is simultaneously intense and strange. The flat patches of colour seen in her pictures – an application of acrylic paint using a fine or broad brush, or airbrush – are inflected via effects of the art materials used, in this case glass beads added to the pigments. Colour is freed from its objective context and becomes a subject in and of itself. Figuratively what she borrows in terms of iconography comes from Pop culture and digital media. She inserts these sources in chromatic arrangements depicting, for example, microorganisms of a scientific nature. Others are akin to maps drawn from spatial imagery such as interstellar views or recordings made by thermal sensors, like the apocalyptic fires seen this summer. Specifically in this series, Donzé has represented for the first time sunflowers, the heliotropic flower par excellence, the particularity of which is to follow the light of the sun from morning to night. By analogy, this surprising floral presence encourages visitors looking at her works to move around when facing them while being on the lookout for shimmering effects of the pigment which unquestionably recall the visual effects of mirages. This monumental series by Natacha Donzé masterfully conjures up the theme of the show and once again launches, if need be, the fertile dialogue between reality and fiction.

The approach to art followed by GINA PROENZA (*1994) is anchored in a relationship to time and space that is especially dense and personal. Her multiform artworks reference both Minimal art and ancestral vernacular practices. Her ability to transgress the codes found in the field of art adds a narrative, even political dimension to her work and opens up an anthropological reading of her pieces. For the Mirage project, Proenza questions the connection between current ecological issues and those in the sphere of contemporary art. Dormant Season and La Tempête are two pieces she did working with the designer and farmer Emma Bruschi, who uses dried plants to produce a range of things, notably textiles. The initial piece refers to the tradition of the Danse Macabre; in it we see a half-human half-animal skeleton done in straw embroidery and squatting as if hard at work. The second piece was also produced using the same technique and borrows certain elements from a painting that the artist considers her first aesthetic shock, The Tempest (1506-1510) by the Venetian artist Giorgione. Proenza is fascinated by this famous picture and how a thunder storm is painted at the heart of an absolutely serene landscape. It is as if that contradiction became for her the only way to grasp the link between nature and culture in her work. L’état des je I, II are unsteady rocking benches that in a way parody the traditional furniture of museum galleries. Inspired by an eponymous painting by Eleonora Carrington that is part of the MCBA collection, these two artworks introduce a playful function thanks to their instability, and a strange sculptural presence through their monumental size. Juger les vers is a video piece based on a corpus of texts chronicling court trials of animals that occurred in French-speaking Switzerland between the 15th and 17th centuries. Indeed, during various famines, certain insects were successively humanised, demonised, recognised as responsible for the destruction of crops and ultimately sentenced by the court. For this piece, the artist analyses these legal records, developing a stroboscopic installation in which all of the words are projected on the wall in alphabetical order. The story of these excommunicated white grubs amounts to a lampoon denouncing the use of language as a coercive tool. In an age when there seems to be widespread pleasure in shutting up things and ideas in one category or another, being hybrid is frightening. Gina Proenza defends the opposite. It is in the fusing of the domains of culture and history that she gleans her ideas and forcefully develops her work.