Exhibition guide

Under the Skin. Vienna 1900

Exhibition guide

Under the Skin. Vienna 1900, from Klimt to Schiele and Kokoschka

2.6 — 23.8.2020

In the Vienna of 1900, a phalanx of artists was to write one of the most significant episodes in the birth of modern art. Rejecting the conventions of academicism in painting and historicism in architecture and the applied arts, these artists were on a mission to lay bare the true identity of human beings in the 20th century and reconcile them with their deep instincts, nature and

the cosmos.

The exhibition offers a new reading of the vast body of work created by these revolutionary artists between 1897 (the founding of the Vienna Secession) and 1918 (the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). The show traces the emergence of a new sensibility expressed by formal, visual work that focuses on skin. By exploring the mysteries of this sensitive surface, the Viennese artists were to redefine modern humans’ connections to the world, everyday objects and their surroundings, buildings and streets.

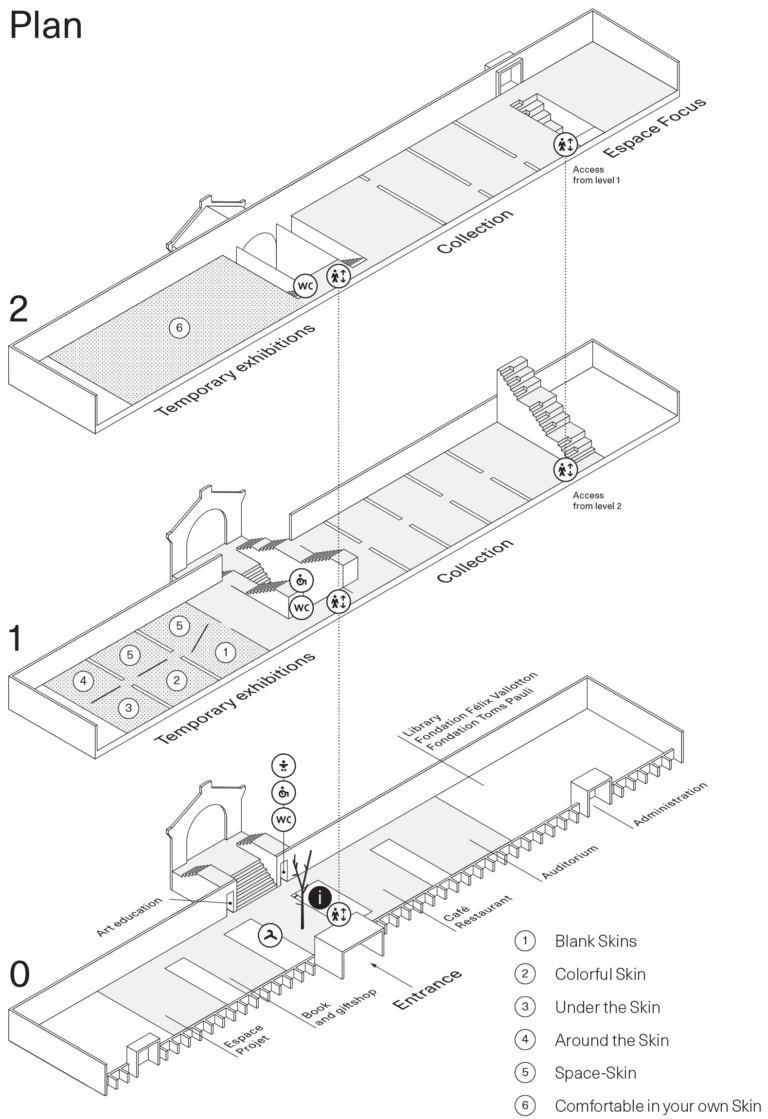

On the first floor you are invited to discover how the Viennese artists made their contribution to modernity by endowing skin with a novel visual expressiveness. The exhibition continues on the second floor, which is devoted to the living environment and its adaptation to the needs of the new human being.

1st floor

Section 1 / Blank Skins

Der Zeit ihre Kunst – Der Kunst ihre Freiheit, or “To the age its art, to art its freedom.” This motto of the Viennese Secession, an association of dissident artists founded in 1897 and presided over by Gustav Klimt, announced a revolution in the capital of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire. As in other European cities, the time had come for Vienna to forge an independent national modern style. The idea was to put an end to the supremacy of academicism and historicism, which were only perpetuating the obsolete values of the aristocracy, and the conservatism of the Society of Austrian Artists.

In 1898, the Secessionists built an exhibition hall. They launched a program of ambitious shows and events that joined the great names of international modernity to the local art scene. They created a review for debating the art questions of the day called Ver sacrum (literally “sacred spring”). A fresh breeze was indeed blowing through the land, awakening minds. It placed this creative impetus under the banner of a season, spring, and an age in life, youth. It was nakedness, of the human body and the façade of buildings stripped of their pompous decorations and brought back to a smooth unadorned whiteness, that initially expressed the common struggle to get back to truth. Around these virginal surfaces, sinuous lines and blocks of uniform colors shaped a kind of brightly colored setting for stylized or geometric motifs.

Section 2 / Colorful Skin

During their training at an academy, artists would take drawing classes working from nude models. They learned to analyze the effects that the play of joints and muscles has on the surface of the body. The model would hold a pose and the same drawing would be worked over and over until it satisfied the instructor. It was only later, in a second phase, that the pupil would be introduced to oil painting, discovering how to obtain a colored rendering of skin tones through thin runny layers of pigment.

From the start of his time at the School of Applied Arts, Oskar Kokoschka fought the static aspect of the poses and their conventional character. Egon Schiele got up from the student’s stool to pace around, leaning in close to his models and moving around them. Occasionally he would only keep cut-off sections of their bodies in his composition. He also broke free of the dictates of how a student was to orient the sheet of drawing paper; some of his sheets can be read in either direction, vertically or horizontally. The main innovation, however, occurred in the realm of color, which was freed at this time from the strictures of realistic representation. The body was covered by a uniform fluid or broken down by zones. Pure tones on the skin indicate points where the skeleton is rubbing against it, the pressure exerted by the organs, the rush of blood beneath the epidermis. They express emotions coming to the surface. In Schiele’s late work, finally, a bright red was occasionally used in spots to mark out erogenous zones.

Section 3 / Under the Skin

Starting in the mid-19th century in Vienna, anatomy became the first and foremost discipline of the medical sciences. Artists, too, were introduced to dissection during their studies at the academy. They would visit the collection of colored wax models on display in the Josephinum Museum. They had classes with professors at the Anatomy Institute, including Emil Zuckerkandl, who began publishing his famous Atlas der topographischen Anatomie des Menschen (Atlas of the Topographical Anatomy of Humans) in 1890.

To take what dissection reveals but the skin hides from the eye and make it perceptible, they would literally delve beneath the epidermis and bring back to the surface the expression of a complex underground life made of bones, nerves, and blood, and brought to a boil by instincts and emotions. In portraits, oil paint became something sculpted and kneaded at the surface of the canvas. The iconographic elements of the martyrdom of both Christ and the saints and their open wounds were reinterpreted in self-portraits in which they express the painful condition of their misunderstood creator. The tattoos of “primitive peoples” were viewed as models of a creative power that had been at work since the dawn of humanity, before the alienation wrought by civilization. The embossed motifs that the Wiener Werkstätte worked on leather book bindings and other leather goods were inspired by the geometric patterns of these tattoos.

Section 4 / Around the Skin

Romanticism had already made the artist an exceptional being endowed with a heightened sensibility and an inner capacity for visionary experiences. In a Vienna steeped in spiritism and occultism, artists ascribed to themselves and their work a sacred mission, that of revealing to modern humans the existence of a reality beyond the senses.

The scientific discoveries of the day, which were piercing the mystery surrounding electricity, magnetism and radioactivity, reinforced this hunch. Photographs of mediums showing the presence of specters or doubles slipping out of their host bodies, fed these artists’ imagination. The illustrations found in the pages of theosophy manuals displaying fields of radiation and colorful vibrations were sources of inspiration for them. The artists who were convinced they could see manifestations invisible to the eyes of the common run of humanity were legion and they set about reproducing the astral envelopes surrounding bodies, the auras and the waves, or the colors and forms they lent to thoughts.

“I paint the light that emanates from all bodies,” Schiele declared. Like Oskar Kokoschka, Richard Gerstl, Max Oppenheimer, and Koloman Moser, Schiele proposed innovative pictorial solutions with whose help he aspired to renew the ties between matter and mind, this world and the hereafter.

Section 5 / Space-Skin

The concept of “space-skin” allows us to talk about the most significant invention of the Viennese Modernists, i.e., a new formal space linking the human body and its inner world with its natural and cosmic surroundings.

Artists abandoned the perspectival space they had inherited from the Renaissance. That is, depth disappeared in favor of joining on the same pictorial plane the different elements of what was being depicted, whether figurative or decorative. In drawing, mother and child, man and woman, a lesbian couple form a single entity and melt into the white of the page thanks to open, vibrant lines. In painting, too, bodies cling to one another, cluster and mass, forming compact blocks. They interlock and are fitted together like pieces of marquetry or like a magma of pigment, until they form a whole, a surface for projections that

is all one.

Completely saturated, the image bespeaks a horror vacui, a fear of empty space, that evinces the effort to rebuild a lost unity. The landscapes of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele are especially characteristic of this solidarity of the pictorial plane. Their square format, breaking with the tradition of the panorama, and their horizon lines, which lie practically outside the picture, reinforce the impression that the motif springs from some arbitrary sampling of the stretched skin of the world.

2nd floor

Section 6 / Comfortable in your own skin

In the field of the applied arts, Vienna’s avant-garde artists tackled reforming the living environment, the space in which daily life plays out, to adapt it to the needs of modern humans. The first to turn his back on historicism and representational furniture, the architect and urban planner Otto Wagner became the leading thinker for the young generation.

In 1903 Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser founded the Wiener Werkstätte, an association of artists and craftsmen that fought mass production while promoting quality in crafts and in the materials employed. Their goal was to create a new style for objects, one that was functional, comfortable and hygienic, and in which decoration added no message to form but rather made clear its destination and its principles of construction. White and black predominated. The motifs evolved towards a geometrical vocabulary, the very opposite of the explosion of vegetal motifs that came with Jugendstil. Furniture takes on a lightness and melts into space. The surface of objects harbors perceptible, tactile patterns.

Adolf Loos, on the other hand, reckoned that modern beauty would spring not from a new style but from artists’ ability to adapt to their patrons and clients. Everyone agreed on one point, however, the importance of a unified design for furnishing interiors, conceived and carried out as a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art.

Timeline

1897

Founding of the Wiener Secession, the Vienna Secession. The earliest members include Gustav Klimt (the first president of the association), Josef Engelhart, Josef Hoffmann, Max Kurzweil, Koloman Moser, Joseph Maria Olbrich, and Alfred Roller.

1898

The Secession holds its first show. The movement’s review, Ver Sacrum, is also launched. Inauguration of its exhibition venue, a building designed by Olbrich..

1899

Opening of the Café Museum (interior designed by Adolf Loos).

1900

Klimt starts spending his summers by the Attersee.

1902

The Secession’s 14th show, this one in homage to Ludwig van Beethoven; Klimt paints a frieze inspired by

the Ninth Symphony.

1903

Hoffmann, Moser, and the industrialist Fritz Waerndorfer found the Wiener Werkstätte, or Viennese Workshops, a cooperative for craftsmen-artists. Klimt mounts a solo show at the Secession.

1904

Ground is broken for the Österreichische Postsparkasse, the Austrian Postal Savings Bank (designed by Otto Wagner).

1905

The “Klimt Group” (Klimt, Hoffmann, Moser, Wagner, and others) officially renounce their membership in the Secession to protest the movement’s naturalist wing.

1907

Moser quits the Wiener Werkstätte and devotes himself to painting. Kokoschka begins working for the Wiener Werkstätte. Klimt takes Schiele under his wing. The Cabaret Fledermaus opens (the interior is appointed by the Wiener Werkstätte under Hoffmann’s direction).

1908

The Kunstschau is held, an exhibition mounted by Klimt’s group in a temporary building (designed by Hoffmann). Kokoschka is introduced to Loos, who soon becomes his mentor. Richard Gerstl commits suicide.

1909

The Internationale Kunstschau is held and includes work by Schiele and Kokoschka, who were invited to exhibit by Klimt. Schiele leaves the Academy of Fine Arts and founds the Neukunstgruppe.

1910

Kokoschka begins a stay in Switzerland, joining Loos there.

1911

Schiele sojourns in Krumau, Bohemia.

1914

Outbreak of World War I.

1915

Schiele is conscripted and sent to Prague. Kokoschka is wounded on the Ukrainian front.

1918

End of World War I. The Austro-Hungarian Empire is formally dissolved. The deaths of Klimt, Wagner, Moser, and Schiele.